This blog first appeared on the ESRC Blog to coincide with Antibiotic Awareness week. In it Helen writes about medical paternalism in the UK as manifested in the continuing insistence on instructing patients who are prescribed antibiotics to ‘complete the course’ in order to avoid developing drug resistance, even though this is known to be scientifically incorrect.

by Helen Lambert

Most of the UK population have grown up with the message that patients must complete their course of antibiotics to stop drug resistance developing. A recent paper in the British Medical Journal caused international controversy by pointing out that far from preventing the emergence of antibacterial resistance, greater exposure to antibiotics increases the risk of acquiring resistant pathogens; and where research evidence exists, shorter courses of antibiotics are mostly (though not always) as effective as longer ones.

Yet this is nothing new; almost two decades ago the Lancet highlighted the fact that drug resistance mostly isn’t created by not ‘completing the course’ but by other mechanisms. Both 1999 and 2017 publications attribute the familiar mantra ‘complete the course’ to fear of undertreating the infection, and both observe that recommended course durations are based on historical convention, and both call for more research (randomised controlled trials) to discover the minimum effective duration of antibiotic treatment for different types of infection. But the extensive media coverage that followed the 2017 paper ignored the problem of missing evidence and focused on the ‘news’ that advice to ‘keep taking the tablets’ is incorrect.

UK medical authorities have continued to oppose the withdrawal of this advice. According to the Royal College of General Practitioners, “The mantra to always take the full course of antibiotics is well-known. Changing this will simply confuse people”, while the British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy states, “Much clearer evidence and advice are needed before changes in policy are considered”. Is it justifiable to give advice which isn’t backed by scientific evidence and may do more harm than good (by exposing individual patients to the acquisition of drug resistance) simply because we don’t know what else to tell people? Explicit acknowledgement that current prescribing conventions are not fit for purpose would strengthen the case that we urgently ‘need to improve our evidence-base on appropriate durations of therapy for particular infections and patient groups.’

Would overturning dogma increase risk to patients?

Doctors worry that if not advised to ‘complete the course’, patients will stop taking antibiotics when they feel better. This assumes people obey instructions on medication use, but decades of social science research show that patients adapt or simply ignore doctors’ advice according to circumstances and personal experience.

In primary care, antibiotics are used to treat illnesses symptomatically – so when patients are (mis)prescribed antibiotics for viral infections, the sooner they stop, the better. For common bacterial infections (except TB), the therapeutic consequences of people stopping antibiotics once they feel better are unknown, but it’s not inconceivable that subjective perceptions reflect effective treatment; after all, subjective wellness is consistently associated with longer survival. Turning the familiar advice on antibiotics ‘on its head’ only relates to people who get antibiotics as outpatients anyway; clinicians decide on type and duration of antibiotic courses for those in hospital.

Are recommendations to seek medical advice helpful?

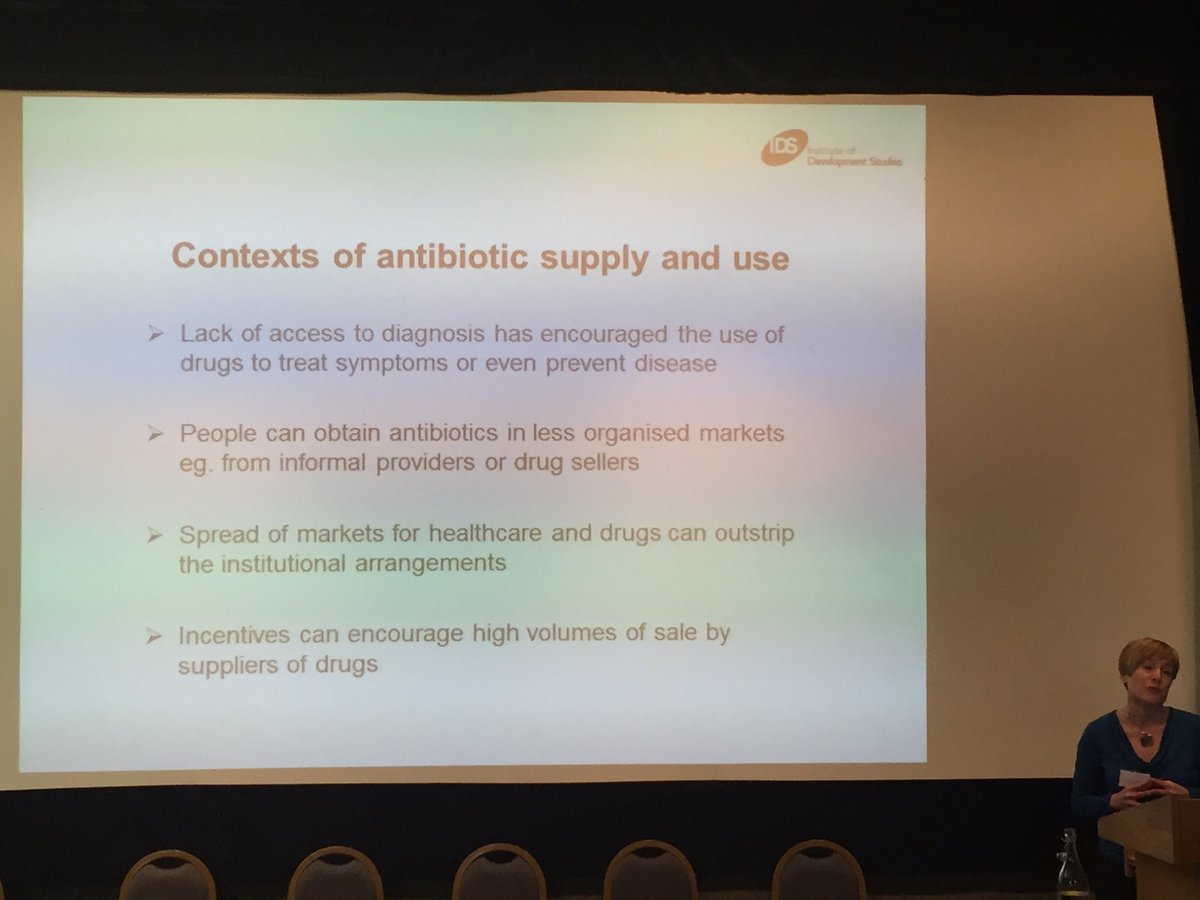

Advice to ‘complete the course’ has been dropped by some authorities including the WHO, in favour of, ‘always follow a doctor’s advice’ or, ‘Only use antibiotics when prescribed by a certified health professional’. Such messages may be appropriate in high-income settings like the UK, but where care from qualified health professionals is lacking or costly, such exhortations are sadly unachievable for many. Self-medication with antibiotics purchased over-the-counter is all too often the cheapest and most accessible option for the poor; and it may be a less important driver of AMR than overprescribing of broad-spectrum antibiotics in private hospitals. Public education about the global challenge of AMR needs to address the reality of different contexts.

Waiting in vain for more evidence

The 1999 article’s author, my father (who died in April, aged 90), told me the journal’s editors added the question mark in its title against his wishes; he had wanted to make a clear statement about the fallacy behind antibiotic prescribing conventions. Eighteen years have seen scant progress in withdrawing advice to complete the course or answering the call for evidence. Trials to compare antibiotic dosages and durations for different infections lack support and funding. The methodology is complex, ethics clearance difficult and pharmaceutical companies have no incentive to demonstrate that shorter courses work as well as longer ones. A recent commentary on the controversy reiterated the need for evidence, concluding with inadvertent irony, ‘We would rather not read the same headline a decade from now’. Now antimicrobial resistance is recognised as a global threat, funding pours into research on diagnostic technologies and novel antimicrobials, while the decision-making needs of doctors and ordinary people remain unmet.

The real controversy lies not in whether advice to ‘complete the course’ is appropriate, but in what to tell patients instead. Lacking information on how long is long enough, too many health professionals fear admitting medical ignorance to their patients. It looks as though the mantra may be secure for a few more years yet – a testament to the tenacity of medical dogma, and the valorisation of basic science and technology innovation over essential clinical, social and population health research.

________________________

Helen Lambert is grateful to Professor Alison Holmes for insightful comments.

You can follow Helen on Twitter @HelenSLambert

Find out more about what the research councils are doing to tackle antimicrobial resistance and the battle to keep our drugs working.

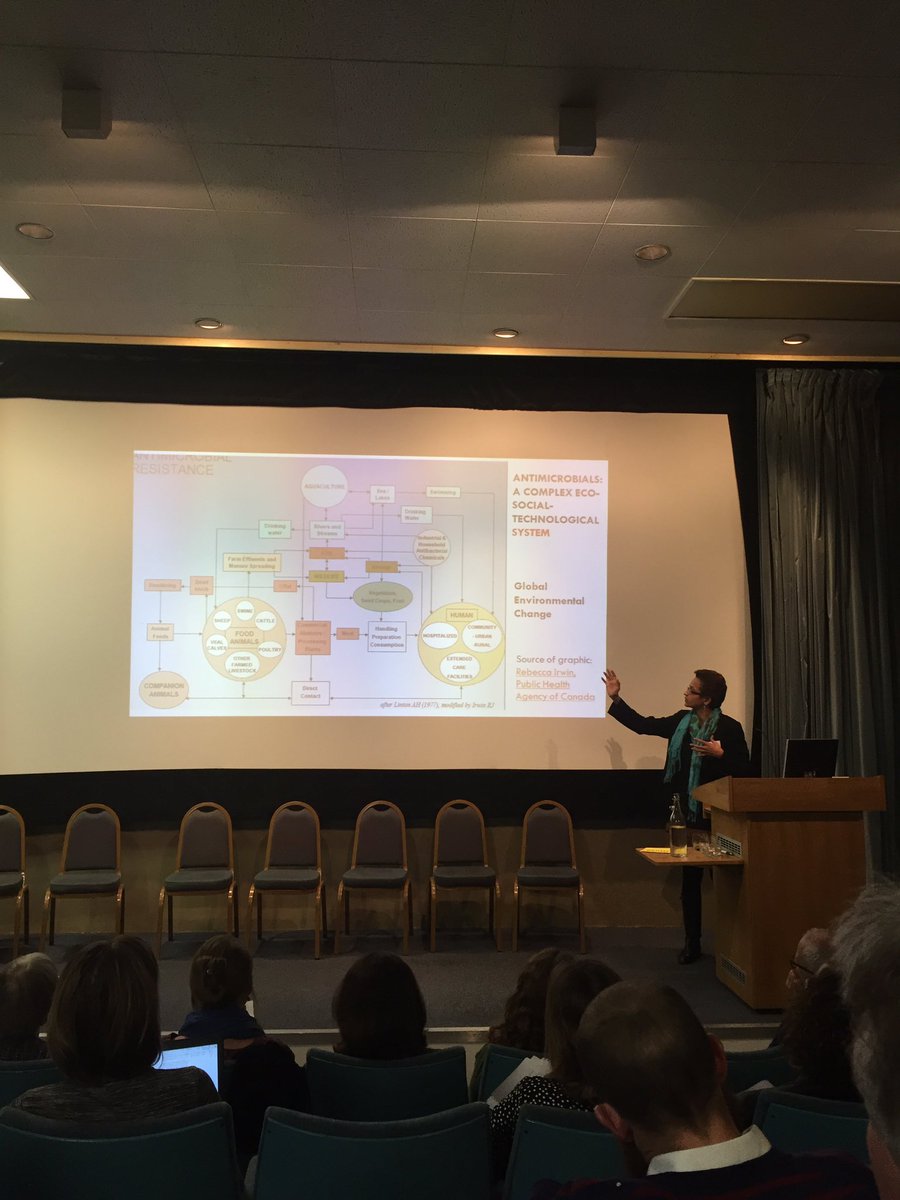

At our second meeting, one of the team bravely admitted that they didn’t understand anything about agent-based modelling, an approach we plan to use in the project. We all recognised similar gaps in our knowledge and expressed anxieties about this – some team members didn’t really understand qualitative research methods, or how antibiotic resistance comes about. I’ve reassured the team that the value of interdisciplinary research is that everyone brings different and valuable expertise and perspectives to the problem. We don’t all need to be experts in everything, instead we need to recognise where we each are experts, and be aware of the extent and limits of our knowledge. But, if we’re going to be able to bring these different perspectives together we all need some level of shared understanding to orient towards the problem. My ‘crib sheet’ folder of key, accessible resources, which has been shared with the team, is one way of trying to help us develop this shared understanding.

At our second meeting, one of the team bravely admitted that they didn’t understand anything about agent-based modelling, an approach we plan to use in the project. We all recognised similar gaps in our knowledge and expressed anxieties about this – some team members didn’t really understand qualitative research methods, or how antibiotic resistance comes about. I’ve reassured the team that the value of interdisciplinary research is that everyone brings different and valuable expertise and perspectives to the problem. We don’t all need to be experts in everything, instead we need to recognise where we each are experts, and be aware of the extent and limits of our knowledge. But, if we’re going to be able to bring these different perspectives together we all need some level of shared understanding to orient towards the problem. My ‘crib sheet’ folder of key, accessible resources, which has been shared with the team, is one way of trying to help us develop this shared understanding.

Joanna Coast

Joanna Coast

Claire Lawrence

Claire Lawrence